A new leak of documents from the offshore service provider at the centre of the Panama Papers scandal reveals the company could not identify the owners of up to three quarters of companies it administered.

Two months after becoming aware of the data breach, Mossack Fonseca was unable to identify the beneficial owners of more than 70% of 28,500 active companies in the British Virgin Islands (BVI) as well as 75% of companies in Panama, according to new documents seen by BBC Panorama.

At the time, BVI law permitted corporate service providers to rely upon intermediaries, banks, legal firms and other offshore service providers overseas to check the identities of the owners, although they were required to provide information if requested by the authorities.

The firm was fined $440,000 (£333,000) by the BVI Financial Services Commission in November 2016 for regulatory and legal infringements of anti-money laundering and other laws.

The new leak contains 1.2 million documents dating from before the Panama Papers went public in April 2016 to December 2017. The data was obtained by Suddeutsche Zeitung which shared it with the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ).

Email correspondence from clients and intermediaries reveal the reaction to the leak, Mossack Fonseca’s desperate attempts to close gaps in their record keeping, and their difficulties doing so. Responding to questions from the firm, one Swiss wealth manager said: “THE CLIENT HAS DISAPPEARED! I CANT FIND HIM ANYMORE!!!!!!”

- Q&A: Panama Papers

- Iceland PM resigns over tax leaks

- Panama Papers: Full coverage

- How tax evasion works

Other correspondence points to the primary reasons many clients were using offshore structures.

One Uruguayan financial planner commented: “…the main purpose of this type of structure has been broken: confidentiality”.

Another intermediary wrote: “… the names of our customers have been known by the authorities of their countries. Thanks to Mossack, customers have to pay incomes taxes.”

According to Margaret Hodge MP, former chair of the UK parliament’s public accounts committee: “This is simply further proof, if any were needed, why we absolutely must have public registers of beneficial owners if we are to stamp out money laundering, tax avoidance, tax evasion and other crimes.”

In the wake of the Panama Papers and under pressure from the UK government, the BVI and other British Overseas Territories have established registers of beneficial ownership for companies in their jurisdictions. But the register relies upon offshore service providers, like Mossack Fonseca, to provide the information. And it is only directly accessible to authorities in the BVI – the public cannot see it.

The BVI denies the register is secret and says it is accessible to the authorities and relevant UK authorities on request within one hour. They say they have been at the forefront of global transparency initiatives.

A spokesman said: “A public register is not a silver bullet. It is not about who can see the information, it’s about the information being verified, accurate, and therefore useful to law enforcement. A verified register is a far more robust and effective approach to ensure transparency than an unverified public register.”

The BVI has resisted pressure for a public register open to scrutiny.

Last month the UK government adopted an amendment to its Sanctions and Anti-Money Laundering Bill to force overseas territories to establish public registers by 2020. The BVI government is considering a legal challenge.

Margaret Hodge, who tabled the amendment with former Conservative minister Andrew Mitchell says: “I would be astounded if the BVI government chooses to waste their own taxpayers’ money litigating against the British parliament – now supported by the British government.”

A spokesman for BVI Finance said that legal advice was “that the imposition of a public register raises serious constitutional and human rights issues. As we have consistently stated, our position is that we will not introduce public registers until they become a global standard”.

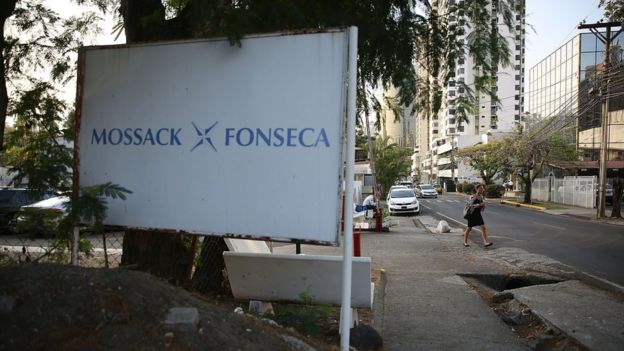

The Panama Papers investigation went public in April 2016 when the BBC and more than 100 other media organisations started publishing stories emanating from 11.5 million documents leaked from Mossack Fonseca.

The investigation was organised by the ICIJ and involved journalists from 76 countries scrutinising internal emails and corporate documents passed to the ICIJ by Suddeutsche Zeitung.

The German newspaper obtained the data from an anonymous source called “Jon Doe”.

The UK investigation was led by BBC Panorama and the Guardian newspaper.

Revelations included documents linking Russian President Vladimir Putin’s close friend, the cellist Sergi Roldugin, to suspected money laundering, Fifa corruption, sanctions busting and systemic tax dodging.

Then Prime Minister David Cameron faced a barrage of questioning over his late father’s offshore investment fund and the prime minister of Iceland was forced to resign following demonstrations about his failure to declare an offshore interest.

Pakistani Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif resigned last year as a result of an investigation prompted by revelations about his family’s offshore financial affairs.

Panamanian police raided Mossack Fonseca’s offices and by the end of 2016 governments and companies in 79 countries had launched 150 inquiries, audits or investigations into the firm, companies it worked with, or its clients.

The new documents show how authorities from around the world, including the UK’s Serious Fraud Office, contacted Mossack Fonseca demanding information about individuals and companies identified in the leak.

Mossack Fonseca’s documents have since been obtained by a number of tax authorities including HM Revenue and Customs which paid an undisclosed sum for the leaked data.

In November 2017, the UK tax authority revealed there were 66 ongoing investigations related to the Panama Papers and that they expected to recover £100m in tax.

Three months ago Mossack Fonseca announced it was closing down citing reputational damage and the actions of the Panamanian authorities. In a statement this month, the company’s founders said that neither they, the firm, nor its employees, were “involved in unlawful acts”.